BUILDERS’ COVID-19 DILEMMA: CONSTRUCTION CONTINUITY VERSUS THE HEALTH RISKS ON JOB SITES

Save lives on your construction sites now, and prevent workers from bringing sickness home, by taking these essential steps thoroughly and immediately.

A commercial buck hoist , the exterior elevator ride crews take to a designated floor to set about working on a scheduled high-rise construction task, can bear loads of up to 8,000 pounds at a clip. About 40 people, gear, materials, etc. can ascend at rates of 300-feet per minute.

For 21 stories, for instance, a buck hoist travels upward 227.4 feet. This converts to about 46 seconds for the ascent. Now, imagine 30 workers–a mash-up of stacked crews of painters, flooring specialists, and interior finish technicians–herding into a buck hoist in a mad dash to wrap up work on the 21st floor of a residential tower.

On a good day, that would not be the best example of keeping a construction workflow staged, cadenced, and on schedule. Still, it’s relatively common practice as job supervisors collide project work-streams as they desperately try to bring a building across the finish line relatively on time.

But that’s not today. “This time’s different” may be a refrain too often spoken. But this time is different.

Here’s the question. Are you willing to bet the health of a person, their family, their community, their circle of acquaintances, etc. on the odds that that 46-second buck hoist trip to the 21st floor will be safe for 30 workers on your job sites?

Some construction project supervisors, from what we hear from places like Atlanta, where dozens of vertical multifamily communities are, in some respects thankfully, plowing ahead in a “business-as-usual” manner, may be so willing.

Plow ahead, yes. But, please, do it differently than you would ever have done it before. These are horrific challenges we face as COVID-19 cases soar! Each of our actions, decisions, and behavior matters. We each have responsibility, accountability, and a say in whether or not the disease spreads in the next day, the next hour, the next 46 seconds.

Here’s what the Center for Disease Control and Prevention says about how COVID-19 spreads. Bottom line, 46 seconds is plenty of time for an uninfected person to pick up the virus, and perhaps take it home with him or her from the job site.

On Tuesday, the National Association of Home Builders called out two specific areas of concern with respect to OSHA compliance on residential construction job sites. One very important one is the known shortage of N95 filtering facepiece respirators (needed so desperately now among healthcare providers on the frontlines of the public health crisis). This suggests sudden impact on the ability to protect construction workers from silica dust and other respirable particles and toxic particulate matter.

Further, and perhaps even more urgent a matter, is OSHA ambiguity on protecting workers on the jobs from the spread of COVID-19 :

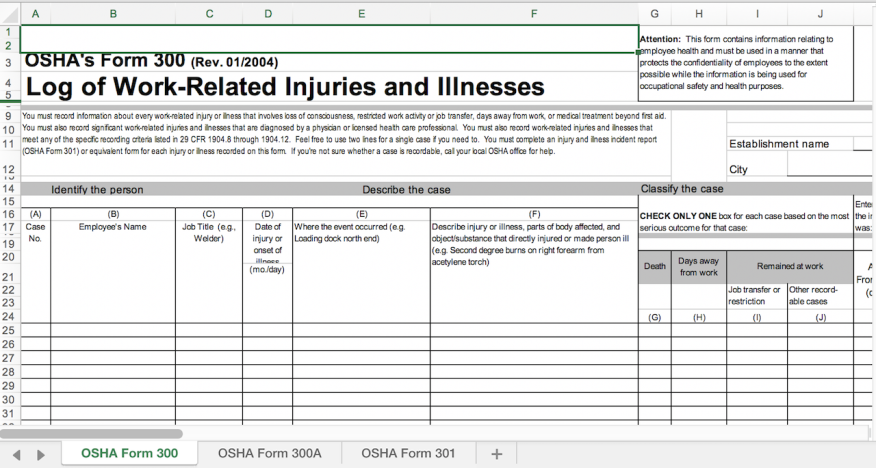

Last year, OSHA issued new rules on reporting injuries and illnesses on the job site. Many are wondering if these new rules apply to coronavirus.

In short, coronavirus is explicitly not exempt from reporting the way a common cold and seasonal flus are. An instance of on-the-job coronavirus transmission may be required to be reported on the OSHA 300 log or on Form 301.

However, according to attorney Brad Hammock of Littler Mendelson P.C., the specific circumstances spelled out in the rule that require reporting of illness will greatly limit the reporting obligations of home builders.

First, it must be shown that the virus was contracted on the job. Also, any hospitalizations that occur 24 or more hours after exposure do not need reporting. In the unfortunate event of a death of a worker less than 30 days after contracting the virus on the job, that event would need to be reported. These narrow requirements will probably result in few cases reported by construction businesses.

The bolded type above is my edit. In other words, construction crews are effectively SOL in terms of deterrent OSHA compliance violations in today’s COVID-19 workplace. A project supervisor who wants to schedule painters, flooring people, and interior finish crews to pile into a buck hoist at the same time to rush to a workflow milestone may have no compunction as he or she does so.

Now, clearly, men and women leading businesses, communities, regions, and the nation have two existential fronts to battle on right now. One, is the novel coronavirus and its public health menace. Two, is our way of life, our livelihoods, the present–not the future–of work itself.

This is an extraordinary responsibility to fall on people, when information, insight, and events unfurl hourly, in minutes’ time, in real-time. What we don’t fully grasp one instant becomes life-and-death clear the next. We can’t fix the fact that we tend to under-appreciate risk for what it is, especially to others. We also may not be able to fix the fact that, as humans, we tend to think others will take responsibility for risk instead of ourselves. What we can do, and must do is to overreact, deliberately, calmly, decisively to take precautions for our own health and safety and that of our people.

Still, we know this. The building sector, and housing, and measures to keep the economy as functional as is humanly possible are vital. We’re cheered to learn that as cities, such as Boston, are exempting residential construction from its overall ban on construction activities.

“We’re encouraged that local officials are putting the critical need for new housing in many of our cities into the ‘essential services’ classification of activities, even as they shut-down many businesses and operations in an effort to contain the spread of COVID-19,” says Paula Cino, vp of Construction, Development, and Land Use Policy at the National Multifamily Housing Council. “While we’re supportive of residential construction exemptions, we’re also messaging and hearing back about measures construction job supervisors’ efforts to make their projects safe and healthy workplaces.”

Cino notes that staging and shift schedule adjustments aimed to reduce the number of crew members on a site, allowing for social distancing, precautions for handwashing, masks, and other measures are becoming common practice on many sites.

Still, she notes, a great deal of the judgment, decision-making, enforcement, and oversight of practices is a local jurisdiction matter. Workers and trade crew company owners have very little say in what practices are altered for the safety and health of their teams. Or not.

“Cleanliness, shift stacking, compliance with silica dust rules, etc. are rare on a good day in good times,” says the owner of an interior finish company currently working on more than $1 million in multifamily projects in one of the nation’s hottest construction markets. “Now, I can’t send my team into the job site with any sense of confidence that anybody’s looking out for their well-being and risk of exposure to COVID-19.”

Forty-six seconds at close quarters with 30 other passengers in a buck hoist traveling 300-feet per minute is a harrowing way to start the day’s work these days.

You can help here.

We’ll get through this. We obviously need to keep people working where we can. We know that housing–more of it now–is multi-dimensionally part of the emergent solution. That residential construction gets recognized as “essential” work and service through the COVID-19 public health crisis is a plus.

But think about this:

We need to do what we can not to inundate an already-stressed out healthcare system with thoughtless or reckless decisions regarding our precious human resource of workers.

Given the likelihood–in the grim clutches the COVID-19 crisis grips us–that the nation’s heading toward a wartime-style mobilization of forces and work projects to restore the economy to a path to health, we need many, many healthy construction crews and workers to drive these projects into motion. Healthy ones.

In the battle for resiliency to sustain continuing development of homes for people, builders face a dilemma. It may look like the choice to save livelihoods and the hard decisions to save lives may conflict with one another. They don’t.

Do what you can to know what’s going on–down to the site level–what’s happening every day, every hour, every 46 seconds–to protect the lives and health of your work crews, their families, and their communities. New York Times columnist David Brooks writes:

The Spanish flu pandemic that battered America in 1918 produced similar reactions. John M. Barry, author of “The Great Influenza,” reports that as conditions worsened, health workers in city after city pleaded for volunteers to care for the sick. Few stepped forward.

In Philadelphia, the head of emergency aid pleaded for help in taking care of sick children. Nobody answered. The organization’s director turned scornful: “Hundreds of women … had delightful dreams of themselves in the roles of angels of mercy. … Nothing seems to rouse them now. … There are families in which every member is ill, in which the children are actually starving because there is no one to give them food. The death rate is so high, and they still hold back.”

This explains one of the puzzling features of the 1918 pandemic. When it was over, people didn’t talk about it. There were very few books or plays written about it. Roughly 675,000 Americans lost their lives to the flu, compared with 53,000 in battle in World War I, and yet it left almost no conscious cultural mark.

Perhaps it’s because people didn’t like who they had become. It was a shameful memory and therefore suppressed. In her 1976 dissertation, “A Cruel Wind,” Dorothy Ann Pettit argues that the 1918 flu pandemic contributed to a kind of spiritual torpor afterward. People emerged from it physically and spiritually fatigued. The flu, Pettit writes, had a sobering and disillusioning effect on the national spirit.

There is one exception to this sad litany: health care workers. In every pandemic there are doctors and nurses who respond with unbelievable heroism and compassion. That’s happening today.

You, too, could be heroes. Just for one day. Just for 46 seconds.